Ships in the Darkness (Greenhouse Noise part 2)

Read part 1 first.

When reflecting on greenhouse noise, I’ve begun thinking about daily work in naval terms. I’m sure LinkedIn would love the analogy. A team is a boat. Its members are the sailors. The organization is a fleet.

But what I find interesting about the analogy is that navigation is a central topic in sailing, not only for an individual team/ship but for the cohesion of the fleet. Will the ships collide? Are they going in the same direction? Are they executing maneuvers in coordination?

Before GPS, naval navigation used various instruments in a process called “dead reckoning”. Wikipedia gives the following definition:

[…] dead reckoning is the process of calculating the current position of a moving object by using a previously determined position, or fix, and incorporating estimates of speed, heading (or direction or course), and elapsed time.

Estimation, speed, calculations – tweak a few words, and it sounds like a book on agile methodologies!

The notorious problem with dead reckoning is compounding error – accuracy is a function over previous measurements and their errors, and without recalibration against “known good” measurements it can become highly inaccurate over larger distances. Regular recalibration is essential for success; again, not unlike agile. GPS obviates this completely, because position (and subsequently bearing) are continuously measured with high accuracy.

Unfortunately, organizational alignment isn’t as well-defined a problem as positioning on the globe, so we may never get our version of a GPS. Even with excellent and responsive metrics and fast feedback cycles, you’ll never know your exact “position” – you can only reduce the range of error and reduce the cost of mistakes. Furthermore, by analogy, positioning is an operational problem for each individual ship/team. But an organization is a fleet – good positional accuracy within each team is a necessary but not sufficient condition for alignment. Even if the ships know exactly where they are, they still need to know their bearings (i.e. where they’re going). They also need the bearings of the other ships in order to coordinate.

How does this relate to noise? Well, I think noise which comes as a result of organizational friction can be compared to difficulty in finding your position and/or bearings as a result of moving together with a fleet. The sea is a violent environment: you need to deal with storms, rocks, currents, etc. These are all sources of noise. But greenhouse noise is the noise which the fleet imposes on itself, simply by trying to sail together.

I recently had a situation which I described to coworker that it was as if I was seeing a rowboat come out of the darkness to deliver some information. But – the mere existance of a rowboat in the open ocean suggested the presence of a larger ship (i.e. “H.M.S Stakeholder”) nearby, which I couldn’t see but knew was there. Which ship was it? Are they a part of the fleet? Do they know where I’m going? Do I know where they’re going? Should I go talk to that ship? Why did they send a rowboat? Did they send a rowboat? Did the rowboat go off on its own mission?

I think this idea captures some of the factors which I believe contribute to greenhouse noise:

-

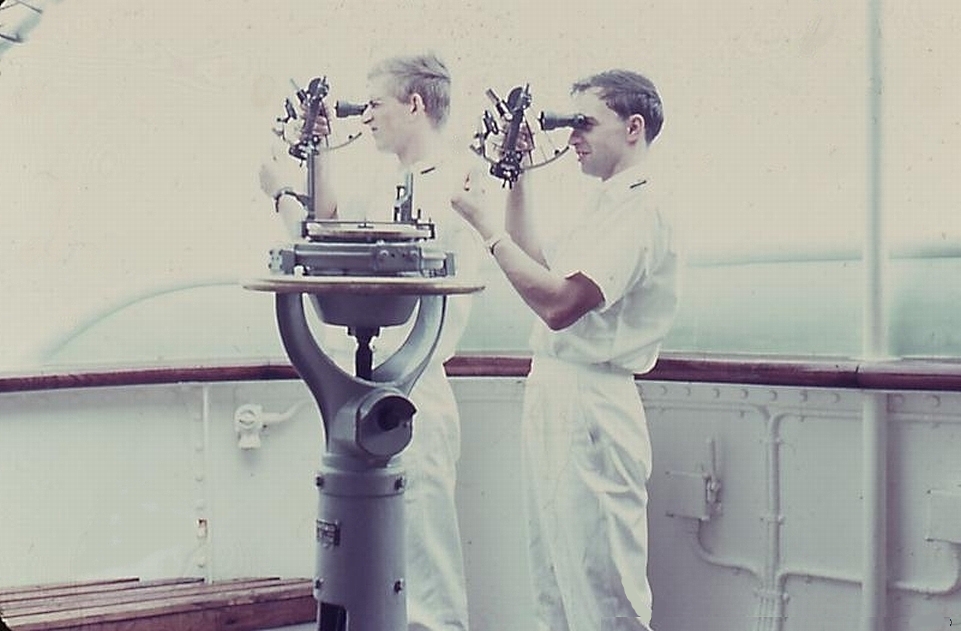

The fog of war shown in the image above arises, I think, from knowledge silos in the organization. This fog of war gets in the way of clear communication. Without clear communication, assumptions start being made and misunderstandings occur.

-

This kind of fog-of-war / knowledge silo situation fosters inefficient alignment. Without the ability to see what’s happening with the other ships/teams, small rowboats float between them in the darkness, crowdsourcing operational visibility and introducing a kind of “telephone” situation.

-

This misalignment creates uncertainty. Ships/teams/stakeholders get in the way of each other. To avoid collisions, they move more cautiously. Sails are reefed and the crews await new orders out of fear of sailing too quickly in the darkness. More rowboats are sent out for clarification.

Coming back to navigation, I think how (un)successfully a team re-calibrates its position compounds all of this since the fleet can’t decide on a new course without a good understanding of where it is. In the worst case you’re still in the realm of dead-reckoning (slow, inefficient, high-risk, with compounding “drift”), and in the absolute worst case you’re dead-reckoning as a fleet using disparate navigational instruments scattered between various ships and reaching consensus using row-boats. In such an environment, communication becomes focused on figuring out where the fleet is instead of where it’s going. Some people want to go North, but others think there are rocks over there. Others want to go South, but worry about hitting the coastline. The fleet itself becomes an obstacle to navigation. And when those ships leave for vacation, you realize it’s open water and all the rowboats have disappeared 🚣.